By Tim Hollister*

Every parent confronts this question: How do we teach our kids about risk, while also protecting them from danger?

I first faced this question in earnest around 2002, when my son Reid turned thirteen. Then the question confronted me, in an entirely different way, after Reid died in a one-car crash in 2006. In the months after his passing, I agonized about how I handled the choices of exposing him to risk and shielding him from danger – or not. My reflection was spurred not by guilt or a need to absolve myself over his driving on one night; my focus was the permissions I had granted and what he had taken from his degrees of freedom. My inquiry was less burdened by the feeling that I had made an obvious mistake than confused by the sense that I hadn’t.

My reflection evolved into a broader perspective on parenting a year later, when I was asked to serve on a task force charged with overhauling Connecticut’s teen driver laws. Our state was in shock from multiple-fatality teen driver crashes, seven deaths in six weeks. Yet no sooner had the task force convened than we began to get pushback against stricter teen driver laws – from parents. A typical message said of our efforts, “While the intention is to reduce the incidence of horrific accidents that maim or kills multiple teens, the fact is that these laws would cause a huge inconvenience.” More extreme but not unique was this: “The fact is that our children have to grow up, and to do that they need to make mistakes, and some of those mistakes will be fatal.”

The impact of these messages was to add a sense of urgency to our work–we needed to tighten our young driver rules, to take decisions about the most dangerous situations out of families’ hands, to make them non-negotiable. (We did so, and since Connecticut’s 2008 overhaul, teen driver fatalities have declined substantially, a remarkable public safety achievement.)

But after my service on the task force, those email stuck with me. I reconsidered my own parenting in comparison to the choices that all parents face. I began to understand that raising kids requires a continual reassessment of when to give kids freedom to explore, and when to shield them before they see for themselves what happens when they touch a power line or lean too far over a cliff. Parenting emerged as a continuum on which the good result is kids returning home, wiser for their experience but unharmed, and the bad result, my own experience, a parent’s worst nightmare.

My need to make sense of all of this led me to learn about the relatively new and not-widely-understood science of delayed brain development. In the past ten years or so, scientists have concluded that the brain is not fully functional until we reach age twenty-two to twenty-five, and the abilities that mature last are the ability to identify risk and to act to avoid it. This is, unfortunately, an immutable characteristic and a difficult fact for parents who want to grant freedom as a way to demonstrate trust.

Another insight was that the allure of convenience in a parent’s busy life is a trap for the unwary. When kids grow to be teens, parents sometimes allow them to face risk for no better reason than it is the parent’s turn to relax. In the same vein, sometimes parents back off from intervening because doing so has the feel of validation that they have done their job, even when that may be an illusion.

Parenting, then, especially of teens, can benefit from regular consideration of when to let them make mistakes or even fail, and when to draw an inviolable line. Sometimes a fatalistic attitude has no place; hopefully, no parent regards mistakes while driving as acceptable. What about school? If we see a child headed for a failing grade, do we intervene or hope for a motivating lesson? How about the Internet and social media? Do we allow kids to be bullied so they will learn how it hurts? What can happen if we don’t intervene? Will my child really learn if things go sideways?

Thinking about parenting as risk assessment may seem like an overly formal way of approaching something that should be intuitive, but the chilling fact remains that far too many children and teens die or are injured from neglected or mistaken evaluation of risk, from eminently preventable causes. Parents would do well to regard their most important responsibility as a continual evaluation of when to grant freedom, when to let kids make mistakes, and when to tug them back from the brink. Parents who simply feel their way forward are rolling the dice – when perhaps they should be counting cards.

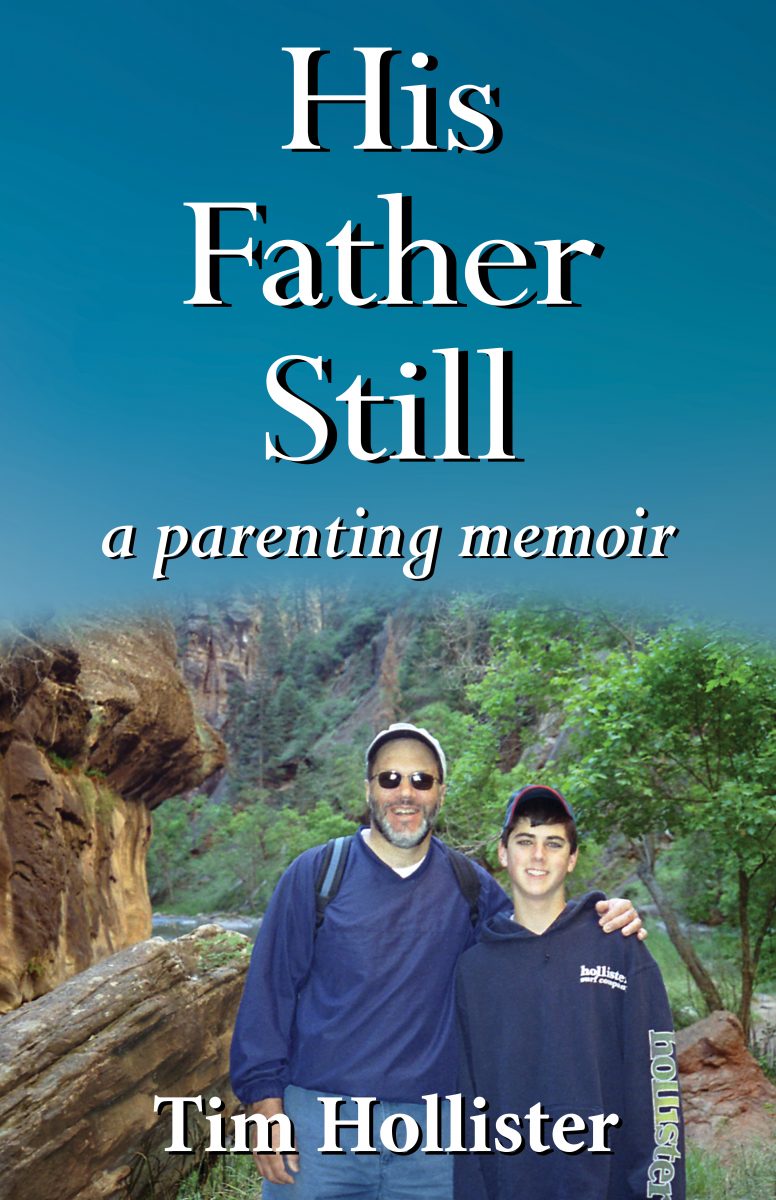

*Tim Hollister, of Hartford, Connecticut is the author of His Father Still: A Parenting Memoir (2015).

This post may contain affiliate links. Please read our disclosure policy here.